A couple of months ago, in the course of one week, about three people asked, “Have you heard of Story Brand?” I’m not a fast reader so a book has got to be pretty great to keep my attention.

After reading the first sentence, I laughed out loud and knew this was going to be a winner. “Customers don’t generally care about your story; they care about their own.”

When I say that this book has shifted my paradigms about marketing forever, I’m not exaggerating. If you own a business, manage a business, if you’re in the marketing, web design, advertising, or creative field, you must take time to read this book. If you’re not, read it anyway and give it to your boss or send it to the CEO, CMO, or your entire team as a gift.

Entire companies around the United States are shifting because of the simple truths laid out in Building a Story Brand. If you care about your company at all, do what countless other business owners out there are doing and read it.

I’ve been in marketing for decades, and what’s strange is, I knew all of these things but never heard anyone describe it the way Donald Miller has.

Don won my heart in 2004 while I was on a road trip around the US with Australian and South African friends. We bought a van with no AC and hit the road for a month. I will never forget lying down in the back seat of that old navy blue Ford Aerostar with the wind whipping through my hair somewhere in maybe Texas or Arizona, reading the first book I had ever enjoyed: Blue Like Jazz.

He writes in an easy-to-understand format but the words are also dense with meaning. I found myself having to take breaks very often to chew on the teaching.

If you love reading, great! Buy it here. I’ve been told by another marketing professional that the audiobook was not a good decision for her because there was too much information to absorb audibly and she wanted to be able to highlight, underline, and make notes in her book.

Some of you, like me, don’t have a ton of time to read. So I’m sharing the excerpts that jumped out to me in the form of a free PDF for you to download and share, as well as right here in this blog series.

Now, the purpose of these excerpts is to give you an idea of what the book is or give you a refresher course if you’ve already read it. It is not meant to substitute Don’s book or his program. My intention is to show you just enough so you’ll buy his book or sign up for their amazing programs and conferences.

Enjoy!

Oh and P.S., here’s a free 5-minute video series from him that’s super helpful as well!

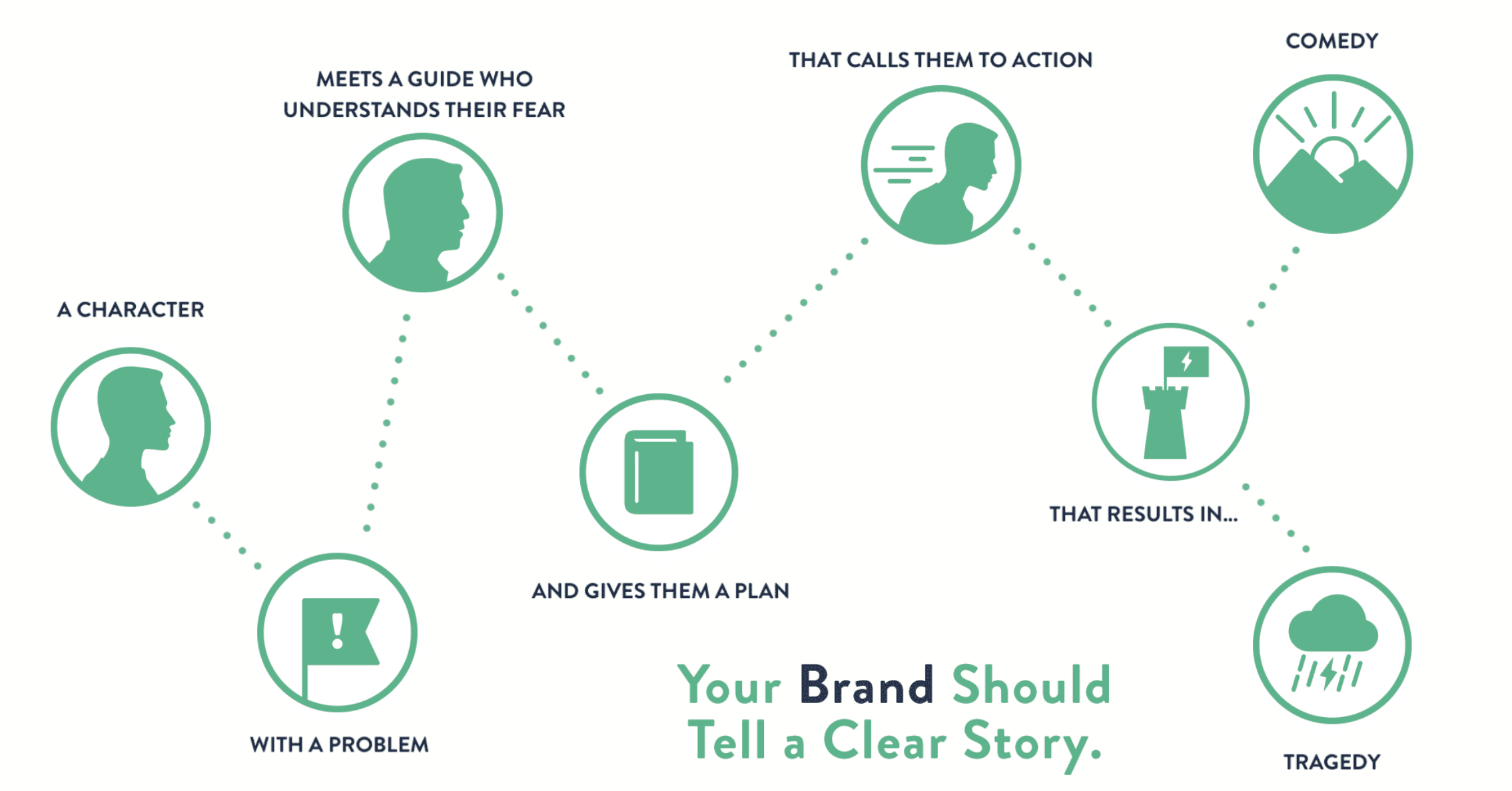

Customers don’t generally care about your story; they care about their own. Your customer should be the hero of the story, not your brand. This is the secret every phenomenally successful business understands.

The human brain, no matter what region of the world comes from, is drawn toward clarity and away from confusion. The reality is we aren’t just in a race to get our products to market; we are also in a race to communicate why our customers need those products in their lives. Even if we had the best product in the marketplace, we will lose to an inferior product if the competitor’s offer is communicated more clearly.

How many sales are we missing out on because customers can’t figure out what our offer is within five seconds of visiting our website?

Pretty websites don’t sell things. Words sell things. And if we haven’t clarified a message, our customers won’t listen.

Nobody will listen to you if you message isn’t clear, no matter how expensive your marketing material may be.

The key is to make your company’s message about something that helps the customer survive and to do so in such a way that they can understand it without burning too many calories.

It was as though he was answering 100 questions his customers have never asked.

What if the Bourne Identity was a movie about a spy named Jason Bourne searching for his true identity but it also included scenes of Borne trying to lose weight, marry a girl, pass the Bar exam, and adopt a cat? The audience would lose interest. When storytellers bombard people with too much information, the audience is forced to burn too many calories organizing the data. As a result, they daydream, walk out of the theater, or in case of digital marketing, click to another site and place an order.

People don’t buy the best products; they buy the products they can understand the fastest.

Customer should be able to answer these questions within five seconds of looking at our website or marketing material: 1: What do you offer? 2: How will it make my life better? 3: What do I need to do to buy? We call this passing the grunt test. The critical question is this: Could a caveman look at your website and immediately grunt what you offer? Imagine a guy wearing a bearskin T-shirt, sitting in a cave by a fire, with a laptop across his lap. He’s looking at your website. Would he be able to grant an answer to the three questions posed? If you were an Aspirin company, would he be able to grunt, “You sell headache medicine, me feel better fast, me get it at Walgreens.” If not, you’re likely losing sales.

Customers are attracted to us for the same reason heroes are pulled into stories: they want to solve the problem that has, in some big or small ways, disrupted their peaceful life. Companies tend to sell solutions to external problems, but customers buy solutions to internal problems. By talking about the problems our customers face, we deepen their interest in everything we offer. If we sell lawn care products, they’re coming to us because they’re embarrassed about their lawn or they simply don’t have time to do the work. If we sell financial advice, they’re coming to us because they’re worried about the retirement plan.

At this point we’ve identified what the customer wants, the problems they’re encountering, and positioned ourselves as their guide. And our customers love us for the effort, but they still aren’t going to make a purchase. Why? Because we haven’t laid out a simple plan of action they can take. Making a purchase is a huge step, especially if our products or services are expensive. What customers are looking for, then, is a clear path we’ve laid out that takes away any confusion they might have about how to do business with us.

Customers do not take action unless they are challenged to take action.

Every human being is trying to avoid a tragic ending. If nothing can be gained or lost, nobody cares. If there’s nothing at stake in a story, there is no story. Likewise, if there’s nothing at stake at whether or not I buy your product, I’m not going to buy the product. Simply put, we must show people the cost of not doing business with us.

Brands that help customers avoid some kind of negativity in life, and let their customers know what that negativity is, engage customers for the same reason good stories captivate an audience: define what’s at stake.

Never assume people understand how your brand can change their lives. Tell them. Offer a vision for how great the customers life could be if they engage your products or services.

As a brand, it’s important to define something your customer wants, because as soon as we define something a customer wants, we pose a question in the mind of a customer: will this brand really help me get what I want?

We need to find something your customer wants. The customers are invited to alter their story in your direction. If they see your brand is trustworthy and reliable, they will likely engage.

Identifying potential desire for your customer opens what is sometimes called a story gap. The idea is that you place a gap between a character and what they want. Moviegoers pay attention when there’s a story gap because they wonder if and how that gap is going to be closed. Hunger is the opening of the story gap and a meal ushers its closing. There is little action in life that can’t be explained by the opening and closing of various story gaps. When we fail to define something our customer wants, we failed to open a story gap. When we don’t open the story gap in our customer’s mind, they have no motivation to engage with us. Defining something your customer wants and featuring it in your marketing materials will open a story gap.

Once a brand defines what the customer wants, they are often guilty of making the second mistake: what they’ve defined isn’t related to the customer’s sense of survival. In their desire to cast a wide net, they define a blob of a desire that is so vague, potential customers can’t figure out why they need it in the first place. When I say survival, I’m talking about the primitive desire we all have to be safe, healthy, happy, and strong.

For business to business companies, offering increased productivity, increased revenue, or decreased waste are powerful associations with the need for a business or an individual to survive and thrive.

Imagine your customer is a hitchhiker. You pull over to give them a ride, and the one burning question on his mind is simply, “Where are you going?” But as he approaches, you roll down the window and start talking about your mission statement, or how your grandfather built this car with his bare hands, or how your road trip playlist is all 1980s alternative. This person doesn’t care. All he wants to do is get to San Francisco.

The goal for our branding should be that every potential customer knows exactly where we want to take them. A luxury resort where they can get some rest, to become the leader everybody loves, or to save money and live better.

If you randomly asked a potential customer where your brand wants to take them, would they be able to answer? Would they be able to repeat back to you exactly what your brand offers? If not, your brand is suffering the cost of confusion.

If we want our customers’ ears to perk up when we talk about our products and services, we should position those products and services as weapons they can use to defeat the villain. And the villain should be dastardly. The villain doesn’t have to be a person, but without question it should have personified characteristics. If we are selling time management software, for instance, we might vilify the idea of distractions. Could we offer a product as a weapon that customers could use to stop distractions in their tracks? Sounds kind of dramatic right? And yet distractions are what is diluting our customers’ potential, wrecking their families, stealing their sanity, and costing them in enormous amounts of time and money. Distractions then, make for great little villains.

Frustration, for example is not a villain. Frustration is how a villain makes us feel. High taxes, rather, are a good example of a villain.

The villain should be relatable. When people hear us talk about the villain, they should immediately recognize it as something they disdain. The villain should be singular. One villain is enough. A story with too many villains falls apart for lack of clarity. The villain should be real. Never go down the path of being a fear monger.

By limiting our marketing messages to only external problems, we neglect principle that is costing us thousands and potentially millions of dollars. That principle is this: companies tend to sell solutions to external problems, but people buy solutions to internal problems. The purpose of an external problem in the story is to manifest an internal problem.

In almost every story the hero struggles with the same question: do I have what it takes? This question can make them feel frustrated, incompetent, and confused. What stories teach us is that peoples’ internal desire to resolve the frustration is a greater motivator than their desire to solve an external problem. By assuming our customer only wants to resolve external problems, we fail to engage the deeper story they are actually living. After they were near collapse, Apple didn’t find their footing until Steve Jobs understood that people felt intimidated (internal problem) by computers and wanted a simpler interface with technology.

If we want our customers’ ears to perk up when we talk about our products and services, we should position those products and services as weapons they can use to defeat the villain. And the villain should be dastardly. The villain doesn’t have to be a person, but without question it should have personified characteristics. If we are selling time management software, for instance, we might vilify the idea of distractions. Could we offer a product as a weapon that customers could use to stop distractions in their tracks? Sounds kind of dramatic right? And yet distractions are what is diluting our customers’ potential, wrecking their families, stealing their sanity, and costing them in enormous amounts of time and money. Distractions then, make for great little villains.

Frustration, for example is not a villain. Frustration is how a villain makes us feel. High taxes, rather, are a good example of a villain.

The villain should be relatable. When people hear us talk about the villain, they should immediately recognize it as something they disdain. The villain should be singular. One villain is enough. A story with too many villains falls apart for lack of clarity. The villain should be real. Never go down the path of being a fear monger.

By limiting our marketing messages to only external problems, we neglect principle that is costing us thousands and potentially millions of dollars. That principle is this: companies tend to sell solutions to external problems, but people buy solutions to internal problems. The purpose of an external problem in the story is to manifest an internal problem.

In almost every story the hero struggles with the same question: do I have what it takes? This question can make them feel frustrated, incompetent, and confused. What stories teach us is that peoples’ internal desire to resolve the frustration is a greater motivator than their desire to solve an external problem. By assuming our customer only wants to resolve external problems, we fail to engage the deeper story they are actually living. After they were near collapse, Apple didn’t find their footing until Steve Jobs understood that people felt intimidated (internal problem) by computers and wanted a simpler interface with technology.

Knowing their customers don’t want to haggle over prices or risk buying a lemon, Carmax’s business strategies aim at you not having to feel lied to, cheated, or worked over in your car buying experiences. The extra problem Carmax resolves is the need for car, of course, but they hardly advertise about cars at all. They focus on their customers internal problems and in doing so, entered one of the least trusted industries in America and created a $15 billion franchise.

Customers felt good about themselves when they walked into a Starbucks. Starbucks was delivering more value than just coffee, they were delivering a sense of sophistication and enthusiasm about life. Starbucks changed American culture from hanging out and diners and bars to hanging out in a local, Italian style coffee shop.

Philosophical problems in the story is about something even larger than the story itself. It’s about the question, “Why.” Why does the story matter in the overall epic of humanity? A philosophical problem can best be talked about using terms like ought and shouldn’t. For example, bad people shouldn’t be allowed to win or people ought to be treated fairly.

In the movie the King’s Speech, the external problem is King George’s stutter. This external problem manifests the internal frustration and self-doubt the king struggles with. He simply doesn’t believe he has what it takes to lead the country. Philosophically though, the stakes are much greater. Because the king must unify his people against the Nazis, the story takes on the philosophical problem of good versus evil.

Is there a deeper story your brand contributes to? Can your products be positioned as tools your customers can use to fight back against something that ought not to be? If so, let’s include some philosophical stakes in our messaging.

Stories are best when they are simple and clear. We are going to have to make choices. Just like in stories, human beings wake up every morning self-identifying as a hero. They are troubled by internal, external, and philosophical conflicts, and they know they can’t solve these problems on their own. The fatal mistake some brands make, especially young brands that believe they need to prove themselves, is they position themselves as the hero in the story instead of the guide. As I’ve already mentioned, a brand that positions itself is a hero is destined to lose.

The crucial mistake Jay Z failed to answer with his music company, Tidal, was the one question lingering in the subconscious of every hero customer: how are you helping me win the day? Tidal existed to help artists when the day, not the customers. And so it failed. Always position your customer as the hero and your brand as the guide. Always. If you don’t, you will die.

The day we stop losing sleep over the success of our business and start losing sleep over the success of our customers is the day our business will start growing again.

If we are tempted to position our brand as the hero, because heroes are strong and capable and the center of attention, we should take a step back. In stories, the hero is never the strongest character. Heroes are often ill-equipped and filled with self-doubt. They don’t know if they have what it takes. They’re often reluctant, being thrown into the story rather than willingly engaging the plot. The guide, however, has already been there and done that. They have conquered the heroes’ challenge in their own backstory. A guide, not the hero, is the one with the most authority. Still, the story is rarely about the guide. The guide simply plays a role. The story must always be focused on the hero, and if a storyteller or business leader forgets this, the audience will get confused about who the story is really about and they will lose interest. People are looking for a guide to help them, not another hero.

Your marketing is facing the wrong direction.

When we empathize with our customers’ dilemma, we will create a bond of trust. People trust those who understand them, and they trust brands to understand them too.

Empathetic statements start with words like, “we understand how it feels to…“ or “nobody should have to experience…“ or “like you, we are frustrated by…“

Expressing empathy isn’t difficult. Once we’ve identified our customers’ internal problems, we simply need to let them know we understand and would like to help them find a resolution. Scan your marketing material and make sure you’ve told your customers that you care. Customers won’t know you care until you tell them.

Customers look for brands they have something in common with. Remember, human brains like to conserve calories, and so when a customer realizes they have a lot in common with the brand, they fill in all the unknown nuances of trust. Essentially the customer matches their thinking, meaning they’re thinking in chunks rather than details.

When a customer is deciding whether to buy something, we should picture of him standing on the edge of a rushing creek. It’s true they want what’s on the other side, but as they stand there, they hear a waterfall downstream. What happens if they fall into the creek? Our customers subconsciously ponder this question as they have with our little arrow over the Buy Now button. What if it doesn’t work? What if I’m a fool for buying this? In order to ease our customers concerns, we need to place large stones in that creek. When we identify the stones our customers can step on to get across the creek, we remove much of the risk and increase their comfort level about doing business with us. It’s as though we are saying, “First, step here. See it’s easy. Then step here, then here, and then you’ll be on the other side, and your problem resolved.”

When we spell out how easy this whole thing is and let them know they can get started in three easy steps, they are more likely to place an order. We must tell them to, 1: Measure your space. 2: Order the items that fit. 3: Install it in minutes using basic tools. Placing stones in the creek greatly increase the chance they will cross the creek. For instance, if you’re selling an expensive product, you might break down the steps like this: 1: Schedule an appointment. 2: Allow us to create customized plan. 3: Let’s execute a plan together.

A post-purchase process plan is best when our customers might have problems imagining how they would use her product after they buy it. For example, 1: Download the software. 2: Integrate your database into your system. 3: Revolutionize the customer interaction. Post-purchase process plan does the same thing pre-purchase process plan does, in the sense that it alleviates confusion. Customer is looking at the wide span between themselves in the integration of a complicated product, there are less likely to make a purchase. But when they reach your plan, they think to themselves, oh, I can do that. That’s not hard, and click by now.

A process plan can also combine the pre-and post purchase steps. For instance, 1: Test drive a car. 2: Purchased the car. 3: Enjoy free maintenance for life.

What steps do I need to take to do business with you? Spell out the steps, and it will be as though you’ve paved a sidewalk through a field. More people will cross the field.

Once you create your process or agreement plan (or both), consider giving them a title that will increase the perceived value of your product or service. For instance, your process plan might be called Easy Installation Plan or The World’s Best Night Sleep Plan. Your agreement plan might be called the Customer Satisfaction Agreement or even Our Quality Guarantee. Titling your plan will frame it on the customers mind and increase the perceived value of all that your brand offers.

At this point in our customer story, they are excited. We have to find a desire, identify their challenges, empathize with their feelings, establish your competency in helping them, and give them a plan. But they need to do one more thing. They need us to call them to action. The reason characters have to be challenged to take action is because everybody sitting in the dark theater knows human beings do not make major life decisions unless something challenges them to do so.

If I wrote a story about a guy who wanted to climb Everest and then one day looked at himself in the mirror and decided to do it, I’d lose the audience. That’s not how people work. Bodies at rest tends to stay at rest, and so do customers. Heroes need to be challenged by outside forces.

The moral of the story is people don’t have ESP. They can’t read our minds and know what we want, even if it seems obvious. We have to clearly invite customers to take a journey with us or they won’t.

When we don’t ask clearly for the sale, the customer senses weakness. Customers aren’t looking for brands that are filled with doubt and want affirmation. They’re looking for brands that have solutions to their problems.

When you help your customer solve a problem, even for free, you position yourself as the guide. The next time they encounter a problem in that area of their lives, they will look to you for help. I’ve never worried about giving away too much free information. In fact, the more generous the brand is, the more reciprocity they create. All relationships are give-and-take, and the more you give to your customers, the more likely they would be willing to give something back in the future. Give freely.

Brands that don’t warn their customers about what could happen if they don’t buy their products fail to answer this “So what?” question every customer is secretly asking.

The last thing I want to be is a fear monger, because it’s true that fear mongers don’t do well in the marketplace. But fear-mongering is not the problem 99.9% of business leader struggle with. Most of them struggle with the opposite. We don’t bring up the negative stakes enough and so the story were telling falls flat. Remember, if there are no stakes, there is no story.

Loss aversion is a greater motivator of buying decisions than potential gains. People are 2 to 3 times more motivated to make a change to avoid a lost and they are to achieve a gain.

We do not need to use a great deal of fear in the story we are telling our customers. Just a pinch of salt in the recipe will do.

When receivers are either very fearful or very unafraid, little attitude or behavior change results. High levels of fear are so strong that individuals block them out. Low levels are too weak to produce the desired effect. Messages containing moderate amounts of fear-rousing content are most effective in producing attitudinal and or behavior change.

The three dominant ways storytellers end a story is by allowing the hero to:

1: Win some sort of power or position.

– Offer access (membership, points, intangible status)

– Create scarcity (offer a limited number of specific items)

– Offer a premium (client titles, preferred, diamond member, perks, privileges)

– Offer identity association (status)

2: Be unified with somebody or something that makes them whole.

– Reduced anxiety (glass cleaners offering satisfaction for a job well done and a feeling of closure about a clean house)

– Will the use of your product to lead to the relief of stress and the feeling of completeness? If so, talk about it and show it in the marketing material

– Reduced workload. Customers don’t have the right tools must work harder because they are incomplete. Do you have a tool to offer to give them what they’re missing?

– More time. Not being able to “fit it all in“ is often perceived by our customers as a personal deficiency. Any tool, system, philosophy, or even person who can expand time may offer a sense of completeness

3: Experience some kind of self-realization that also makes them whole.

– Inspiration. If an aspect of your brand can offer or be associated with an inspirational feat, open the floodgates. Many brands like Redbull or Under Armor have associated themselves with athletic and intellectual accomplishment and thus a sense of self-actualization.

– Acceptance. Helping people except themselves as they are isn’t just a thoughtful thing to do, it’s good marketing.

– Transcendence. Brands that invite customers to participate in a larger movement offer a greater, more impactful life along with their products and services.

Think of all this as closing the story loop.

Brands that participate in the identity transformation of their customers create passionate brand evangelists.

A few important questions we have to ask ourselves when we are representing our brand are: what does your customer want to become? What kind of person do they want to be? What is their aspirational identity?

Example, a writer buying a Gerber knife made for adventure. There aspirational identity was to be adventurous and brave and Gerber marketing help them feel that.

The best way to identify an aspirational identity that our customers may be attracted to is to consider how they want their friends to talk about them. Think about it. When others talk about you what do you want them to say? How we answer that question reveals who it is we’d like to be. It’s the same for our customers. As it relates to your brand, how does your customer want to be perceived by their friends? And can you help them become that kind of person? Can you participate in their identity transformation?

If you offer executive coaching, your clients may want to be seen as competent, generous, and disciplined. If you sell sports equipment, your customers likely want to be perceived as active, fit, and successful in their athletic pursuits. Once we know who our customers want to be, we will have language to use in emails, blog post, and all matter of marketing material.

Being the guide is more than a marketing strategy; it’s a position of the heart. When the brand commits itself to their customers journey, to helping resolve their external, internal, and philosophical problems, and then inspires them with an aspirational identity, they do more than sell products… they change lives. And leaders who care more about changing lives than they do about selling products tend to do a good bit of both.

Brands that realize their customers are human, filled with emotion, driven to transform, and in need of help truly do more than sell products, they change people.

Examples of aspirational identities:

Pet food brand

From: Passive dog owner

To: Every dogs hero

Financial advisor

From: Confused and ill-equipped

To: Competent and smart

Have you thought about who you want your customers to become? Participating in your customers’ transformation can give new life and meaning to your business. When your team realizes that they sell more than products, that they guide people toward a stronger belief in themselves, then their work will have a greater meaning. Spend some time thinking about who you want your customers to become. How can you improve the way they see themselves? How can your brand participate in your customers transformational journey? Let’s do more than help our heroes win; let’s help them transform.

Five things the website should include:

1. An offer above the fold. Short, enticing, and exclusively customer-centric. One short sentence to help viewers understand what you offer. Viewers need to know what’s in it for them right when they read the text.

2. Obvious calls to action. Either in the top right or in the center of the screen above the fold. Different from any other color on the side, preferably brighter and all CTA buttons should look the same. If there is a secondary call to action, put it in a less bright button next to the main one.

3. Images of success. In general we need to communicate a sense of health, well-being, and satisfaction with our brand. The easiest way to do this is by displaying happy customers. If people come to our website and see pictures of our building, we’re wasting some of their mental bandwidth on meaningless messages.

4. A bite-sized breakdown of your revenue streams. A common challenge for many businesses is that they need to communicate simply about what they do but they’ve diversified the revenue stream so widely that they don’t know where to start. Find an overall umbrella message that unifies your various streams. Once we have an umbrella message, we can separate the divisions using different web pages. The key is clarity.

5. Very few words! People don’t read websites anymore, they scan them. A person has to hear something or read something many times before they process the information, so we want to repeat our main call to action several times. It there’s a paragraph above the fold in your website, it’s being passed over, I promise. As customer scroll down your page, it’s OK to use more and more words, but by more and more, I really mean a few sentences here and there. If you do want to use a long section of text to explain something, just place a little read more link at the end of the first or second sentence.

*Notes in this document are quotes that have been compiled from Donald Miller’s book and may have inaccuracies as compared to the original text. They in no way reflect the thoughts or opinions of Truman Marketing Group, LLC, but solely from Donald Miller and his book, Building a Story Brand. This document’s only intent is to share excerpts from Donald Miller’s book to those who want a quick, overall understanding of the book, or need a refresher for themselves.